Taking action:

Eliminating racial disparities in infant mortality

For many years, Ohio’s infant mortality rate has been higher than most other states. Ohio’s policymakers and health leaders have acted on this issue through multiple advisory committees, collaborative efforts, investments, legislation and other policy changes. For example, the Ohio General Assembly passed Senate Bill 332 in 2017, which implemented recommendations from the Ohio Commission on Infant Mortality’s 2016 report.

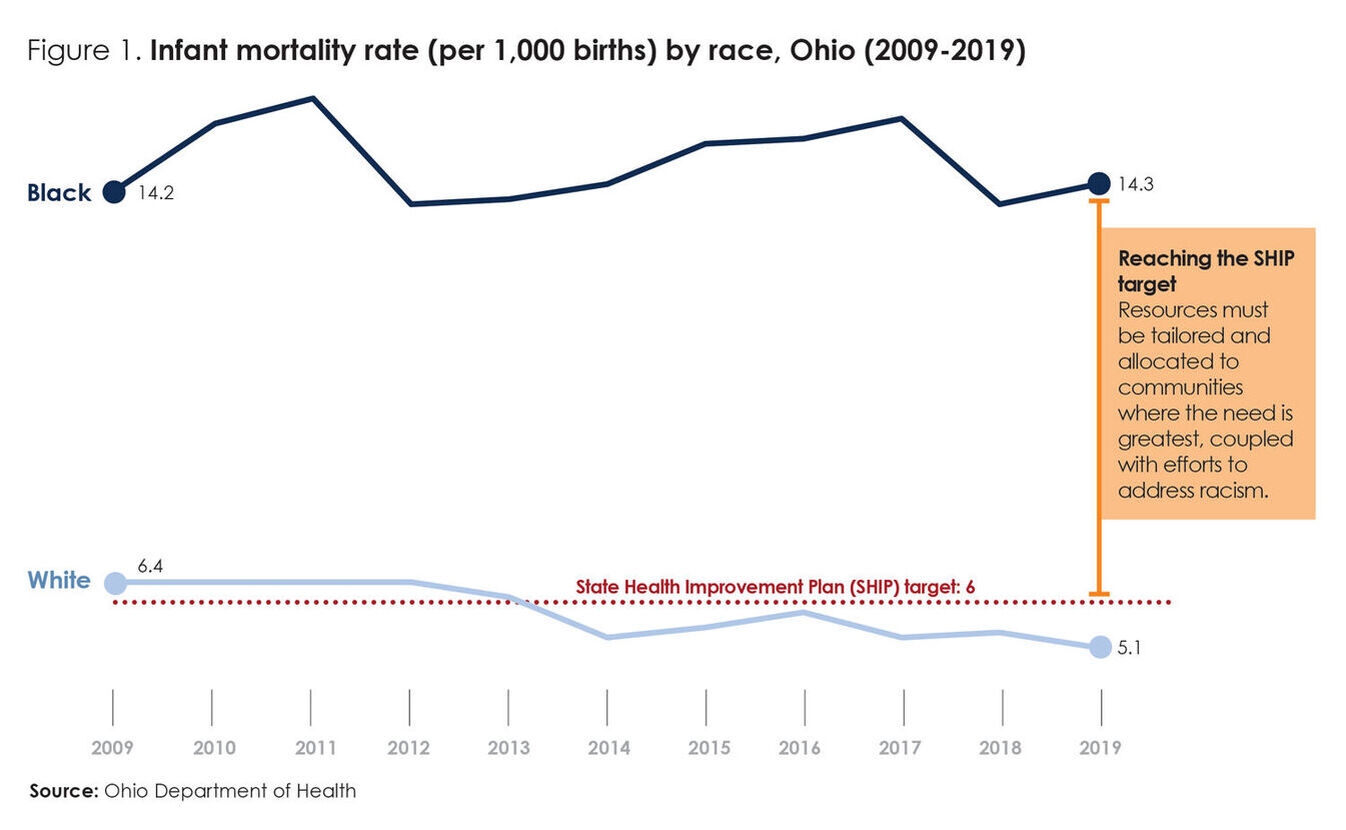

These efforts contributed to a 10% decline in the overall infant mortality rate from 2009 to 2019.1 However, racial disparities in Ohio’s infant mortality rate have increased. In 2019, the Black infant mortality rate was nearly three times higher than the white rate.2

In December 2020, Governor DeWine announced the creation of a new task force focused on eliminating racial disparities in infant mortality by 2030. The task force will host listening sessions in 11 counties, providing an opportunity for members to learn about promising programs, evaluation results and barriers to improving maternal and infant health for Black families.

Previous efforts have generated recommendations based on data and evidence that can be drawn upon to inform the task force’s work. These recommendations highlight the need to maintain access to high-quality health care, while also implementing and intensifying efforts to dismantle racism and improve community conditions that contribute to poor birth outcomes for Black families.

Fact sheet racial disparities

What is the scope of the problem?

Over the past decade, Ohio has seen troubling Black infant mortality trends (see figure 1). Data indicates that:

- In 2019, the Black infant mortality rate (14.3 deaths per 1,000 live births) was nearly three times higher than the white infant mortality rate (5.1).3

- Over the past decade, Ohio’s Black-white infant mortality disparity increased by 26%, from 2.2 in 2009 to 2.8 in 2019.4

- Only five states have a higher Black infant mortality rate than Ohio (among 37 states with 2018 Black infant mortality data available).5

- In 2018, Ohio’s Black infant mortality rate was more than twice that of Colorado, the state with the lowest Black infant mortality rate (6.1).6

- Although poverty is a contributing factor to infant mortality, racial disparities in infant mortality persist even when taking factors such as income and education into account. In 2017 and 2018, the Black-white disparity in infant mortality for Ohioans with bachelor’s degrees or more education was 2.6, which is greater than the Black-white disparity in infant mortality for Ohioans with high school diplomas or less education (1.9).7

What can drive change?

To drive change and eliminate Ohio’s racial disparities in infant mortality, the evidence indicates that the following should be taken into account:

Racism is a primary driver of racial disparities in infant mortality.

The evidence is clear that racism is a primary driver of racial disparities in infant mortality.

Racism can manifest directly and indirectly across all levels of society to impact maternal and infant health. This includes at the individual level (e.g., internalized and interpersonal racism) and systemically (e.g., institutional and structural racism).8 For example:

- Maternal toxic stress contributes to poor birth outcomes.9 Caused by repeated exposure to traumatic events, including racial discrimination, toxic stress results in physical and mental health problems that last throughout one’s life.10 Racism and toxic stress are linked to preterm and low-weight births — leading causes of infant mortality.1111

- Racially-driven implicit bias in health care can result in, among other things, the widespread misdiagnosis of conditions and diseases in Black patients and the health concerns, complaints and questions of Black patients being taken less seriously by clinicians.12

Racism is a system that categorizes and ranks social groups into races and differentially distributes resources and opportunities to those groups based on their perceived inferior or superior ranking. Racism results in the devaluation and disempowerment of racial groups that are classified by society as inferior.13

Access to high quality health care is necessary, but not sufficient.

Improvements to factors beyond access to health care are needed to reduce racial disparities and infant mortality overall. Researchers estimate that, of the modifiable factors that impact overall health, 20% are attributed to clinical care (e.g., healthcare access and quality) and 30% to health-related behaviors (e.g., smoking, healthy eating). The remaining 50% are attributed to community conditions, such as housing, transportation, education and employment.14

For example, living in old, poorly maintained and/or overcrowded housing can make it harder to implement safe sleep practices, cause ongoing toxic stress and increase exposure to hazards, including lead and pests. Additionally, families in low-income households often have difficulty affording basic necessities like healthy food. Poor nutrition is a risk factor for low birth weight and preterm birth.15

Infant mortality disparities are also fueled by systems, policies and practices that disadvantage communities of color, resulting in inequities across community conditions. Compared to white Ohioans, Black Ohioans are:

- 2.5 times more likely to live in poverty

- 2.3 times more likely to live in poor-quality housing

- 2.7 times less likely to graduate high school16

Pregnancy is not the only period of time that matters for infant health.

The health of mothers before pregnancy can have a greater impact on disparities in birth outcomes than the nine months of gestation.17 Prenatal care, case management and care coordination during pregnancy can be “too little, too late” in addressing the root causes of racial disparities in birth outcomes, especially when there are limited community resources to which prospective parents can be connected.

Traumatic events experienced early in life, particularly during sensitive developmental periods in early childhood, have significant impacts on physical and mental health later in adulthood.18 According to HPIO’s Health Impact of ACEs in Ohio brief, Black Ohioans are 1.3 times more likely than white Ohioans to be exposed to multiple adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Ohioans exposed to multiple ACEs are more likely to experience poor health-related outcomes, including depression, respiratory conditions, smoking and heavy drinking – factors that increase the risk for infant mortality.19

What can Ohio do going forward?

High infant mortality rates and racial disparities are not inevitable. State and local policymakers have many options to address racism and the inequitable community conditions that contribute to poor maternal and infant health. HPIO has facilitated initiatives that brought together stakeholders from across the state to prioritize evidence-informed strategies to address key drivers of health beyond clinical care. Many of the recommendations in these reports have not yet been implemented:

A New Approach to Reduce Infant Mortality and Achieve Equity

127 specific policy recommendations to improve housing, transportation, education and employment for communities at risk of infant mortalityState Health Improvement Plan

17 strategies to reduce preterm birth and infant mortality, plus strategies to improve housing affordability and quality and reduce povertyConnections between Racism and Health

Framework for taking action to eliminate racism and advance equityCOVID-19 Ohio Minority Health Strike Force Blueprint

35 recommendations to eliminate racial and ethnic disparities in health outcomes and improve overall well-being for communities of color

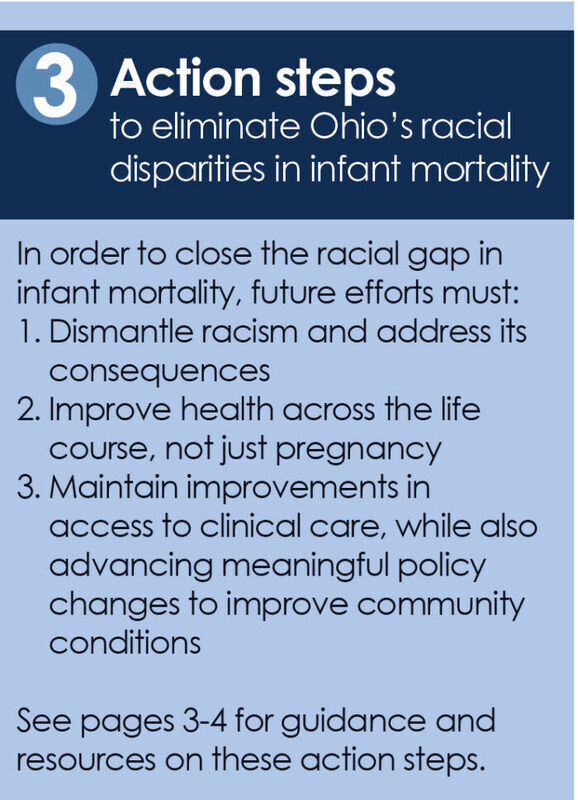

Common themes from these reports indicate that the following steps are needed to make meaningful progress on racial disparities in infant mortality:

- Dismantle racism and address its consequences. Acknowledge racism as a health crisis and help families build resilience in the face of trauma, toxic stress and the cumulative impact of racism across generations. Eliminate racist policies and practices, rebuild community trust and extend and share power with communities of color. Tailor programs and policies and allocate resources to meet the needs of Black families.

- Improve health across the life course, not just pregnancy. Implement policies and programs that promote the health of Black Ohioans, including school-based health services, tobacco prevention and cessation and access to healthy food and physical activity.

- Maintain improvements in access to clinical care, while also advancing meaningful policy changes to improve community conditions. Recognizing that conditions such as housing and income are foundational for family well-being, implement policy changes that help Black families maintain stable housing and self-sufficient employment.

Many groups and initiatives across Ohio are doing important work to address infant mortality, including the Ohio Commission on Infant Mortality, the Ohio Collaborative to Prevent Infant Mortality, Ohio Equity Institute and various regional initiatives, such as CelebrateOne, Cradle Cincinnati, First Year Cleveland and Full Term First Birthday Akron.

Moving forward, state policymakers and other leaders can support these initiatives and act on existing recommendations to address a broader range of factors that drive Ohio’s racial disparities in infant mortality.

What works to improve community conditions?

Examples of evidence-informed policies to address housing, employment and income

To maximize impact on racial disparities in infant mortality, community engagement and outreach to ensure that Black families can access these policies, programs and services is critical.

Improve access to affordable housing

- Collateral sanctions in housing: Reduce legal barriers that prevent people with criminal records or past evictions from renting housing units by eliminating excessive sanctions, reducing rental restrictions and providing access to landlord-tenant mediation and legal aid services

- Rental assistance: Provide rental and utility assistance to families at high risk of infant mortality, including expansion of the Healthy Beginnings at Home program which provides rental assistance and wrap-around housing stabilization services for pregnant women

Support self-sufficient employment and income - Childcare subsidy: Increase eligibility to 200% of the federal poverty level for publicly funded child care and increase the reimbursement rate paid to child care providers

- Collateral sanctions in occupational licensing and hiring: Reduce legal barriers that prevent people with criminal records from getting jobs by eliminating excessive sanctions, expanding use of Certificates of Qualification for Employment and other criminal justice reforms

- Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC): Make Ohio’s state EITC refundable

- Leave policies and employment benefits: Offer incentives to employers, primarily those with part-time and/or low-wage workers, who choose to offer employment benefits, such as paid family leave, sick leave and work schedule predictability

- 2019 Infant Mortality Annual Report. Ohio Department of Health, 2020. https://odh.ohio.gov/wps/portal/gov/odh/know-our-programs/infant-and-fetal-mortality/reports/2019-ohio-infant-mortality-report

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- HPIO analysis of data from CDC WONDER. Accessed Jan. 8, 2021. https://wonder.cdc.gov/lbd-current.html

- Ibid.

- HPIO analysis of data from CDC WONDER. Accessed Jan. 12, 2021. https://wonder.cdc.gov/lbd-current.html

- Race Reporting Guide: A Race Forward media reference. Race Forward, 2015. https://www.raceforward. org/reporting-guide

- Lu, Michael C. and Neal Halfon. “Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Birth Outcomes: A Life-Course Perspective.” Maternal and Child Health Journal 7, no. 1 (2003): 13-30. doi:1023/A:1022537516969; see also Kramer, Michael R. and Carol R. Hogue. “What Causes Racial Disparities in Very Preterm Birth? A Biosocial Perspective.” Epidemiologic Reviews 31, no. 1 (2009): 84-98. doi: 10.1093/ajerev/mxp003

- Shern, David L., Andrea K. Blanch and Sarah M. Steverman. The Impact of Toxic Stress on Individuals and Communities: A Review of the Literature. Mental Health America, 2014.

- Goosby, Bridget J and Chelsea Heidbrink. “Transgenerational Consequences of Racial Discrimination for African American Health.” Sociology Compass 7, no. 8 (2013): 630-643. doi:10.1111/soc4.12054

- Shavers, Vickie L. and Brenda S. Shavers. “Racism and Health Inequity among Americans.” Journal of the National Medical Association 98, no. 3 (March 2006): 386–96.

- Williams, David R. and Selina A. Mohammed. “Racism and health I: Pathways and scientific evidence.” American behavioral scientist 57, no. 8 (2013): 1152-1173

- Booske, Bridget C. et al. County Health Rankings Working Paper: Different Perspectives for Assigning Weights to Determinants of Health. University of Wisconsin Public Health Institute, 2010.

- Kramer, Michael R. and Carol R. Hogue. “What Causes Racial Disparities in Very Preterm Birth? A Biosocial Perspective.” Epidemiologic Reviews 31, no. 1 (2009): 84-98. doi: 10.1093/ajerev/mxp003

- Health Policy Institute of Ohio. 2019 Health Value Dashboard Equity profiles. April 2019.

- Lu, Michael C. and Neal Halfon. “Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Birth Outcomes: A Life-Course Perspective.” Maternal and Child Health Journal 7, no. 1 (2003): 13-30. doi: 10.1023/A:1022537516969

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs): Leveraging the Best Available Evidence. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2019.

- Health Policy Institute of Ohio. “Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACES): Health impact of ACEs in Ohio,” August 2020; Health Policy Institute of Ohio. “A new approach of to reduce infant mortality and achieve equity,” December 2017.

By:

Amy Bush Stevens, MSW, MPH

Reem Aly, JD, MHA

Jacob Santiago, MSW

Published On

January 21, 2021

Download Publication

Download Publication