What Works to Increase Self-Sufficient Employment

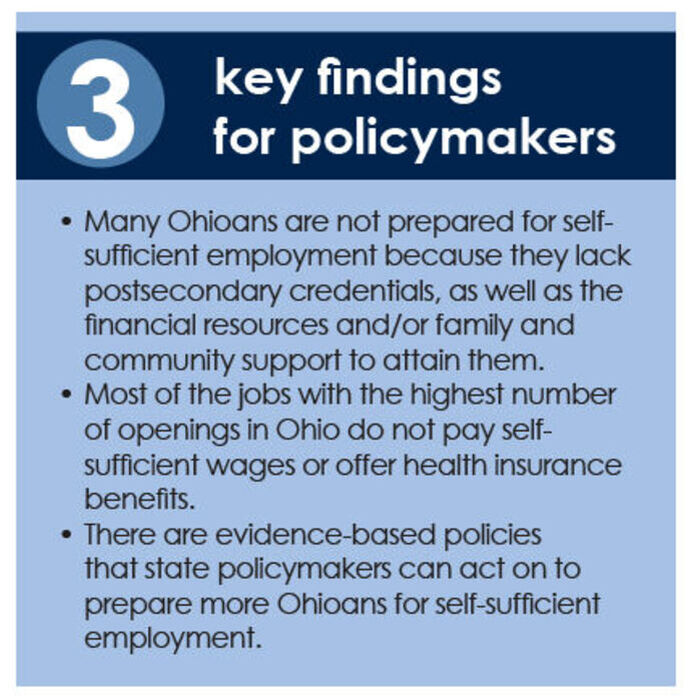

The challenge

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) is encouraging states to test work requirements as a strategy for improving

the health of working-age, non-pregnant adult beneficiaries who are not eligible for Medicaid on the basis of a disability. There is clear evidence that employment is an important determinant of health, and that jobs that pay a sufficient wage contribute to better health. The relationship between employment and health is complex and the direction of causality is unclear. However, there are aspects of employment, like higher wages, that are associated with improved health outcomes.

Postsecondary education continues to be the most important determinant of positive employment outcomes over a lifetime. However, many adults in Ohio, particularly those who may be subject to new and enhanced work requirements, do not have postsecondary education and lack the high-school diploma, financial resources and/or family and community support to get one. For these adults, the journey to self-sufficiency often requires additional support from policies and programs implemented in the public and private sectors.

This policy brief is a resource for policymakers who would like to implement and strengthen evidence-based policies and programs for Ohioans facing barriers to self-sufficient employment.

Background

There are clear connections between income and health. Groups with higher incomes tend to experience better mental and physical health outcomes than groups with lower incomes. Having an income sufficient to meet basic needs makes it easier to avoid and treat health problems. Physical and mental health challenges also impact the type of work people can do.

Status of employment in Ohio

- In 2017, Ohio’s annual average unemployment rate was 5 percent, which was higher than the U.S. rate of 4.4 percent, and there are some Ohio counties where the unemployment rate was much higher.

- In May 2017, about 37 percent of Ohio workers were employed in occupations that paid a median wage of less than $15 per hour.

- About 23 percent of adult workers in Ohio are employed part-time. Part-time workers are less likely to have access to employer-sponsored health insurance benefits than full-time workers.

- In 2016, only 35 percent of Ohio adults had earned a postsecondary degree. Low educational attainment is associated with a lower likelihood of employment and a higher likelihood of employment in jobs that pay lower wages and offer fewer benefits.

Policies and programs that work

There are evidence-based workforce policies and programs that can help people move up the ladder to self-sufficiency. These programs include career-technical education (CTE), GED certificate programs, publicly funded child care (PFCC) subsidies and the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC).

Ohio has implemented many of the policies and programs that increase self-sufficient employment, but not all Ohioans who could benefit from these programs have access to them. For example:

- Some workforce support programs geared toward youth, including some secondary CTE sites, have waitlists.

- Some low-income Ohioans face barriers to earning a GED, such as the increased cost of the test and required computer-based testing.

- Some income support policies create benefit cliffs, which can discourage recipients from seeking employment and/or wage increases. Examples of such policies include the 10 percent cap on the Ohio EITC and the 130 percent of federal poverty level (FPL) benchmark for PFCC subsidies.

State policy options

By seizing opportunities to strengthen supports for Ohio learners and jobseekers, policymakers can increase the likelihood that Ohioans with low incomes successfully engage in work and eventually become self-sufficient.

State policymakers can:

- Increase capacity for secondary and postsecondary career-technical education programs by:

- Incentivizing businesses to partner with and provide financial support to career-technical education programs

- Working with schools and career-technical planning districts to re-evaluate and streamline teacher credentialing requirements

- Providing additional incentive-based resources for under-subscribed career-technical education programs, especially those in career areas that provide self-sufficient employment, with the goal of increasing enrollment in those programs

- Complete an actionable evaluation of the Comprehensive Case Management and Employment Program (CCMEP), including an evaluation of:

- Capacity of provider agencies and case managers

- Engagement of the target population

- Alignment of performance standards and outcomes with the needs and abilities of program participants

- Outcomes related to increasing employment and earnings for youth ages 14-24

- Expand and continually improve alternatives to the GED, including the Adult Diploma Program, the 22+ Adult High School Diploma Program, HiSET and TASC, as well as preparation services for high school equivalency tests provided by Aspire (formerly ABLE) programs.

- Expand the state Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), lift the existing cap on the credit, make it refundable and/or expand the credit to non-custodial parents.

- Increase funding for publicly funded child care (PFCC), restore eligibility limits to 200 percent FPL and expand access by increasing reimbursement rates paid to child care providers.

- Conduct regular evaluations of, and collect additional data and information on, workforce programs funded at the state and federal levels, including waitlist information and participant characteristics, including race and ethnicity.

By:

Hailey Akah, JD, MA

Zach Reat, MPA, HPIO

Published On

August 27, 2018

Table of Contents

Download Publication

Download Publication